Intonation

In

chapter 6, the use of pitch as a phonetic feature was discussed in reference to

tone languages and intonation languages. In this chapter we have disscused the

use of phonetic features to distinguish meaning. We can now see that pitch can

be a phonetic feature in languages such as Chinese, or Thai, or Akan. Such

relative pitch are referred to phonologically as contrasting tones. We also

pointed out that there are languages that are not tone languages, such as

English. Pitch may still play an important role. It is the pitch contour or

intonation of the phrase or sentence that is important.

In

English, syntactic differences may be shown by different intonation contours.

We say John is going as a statement with a falling pitch, but as a question with

the pitch rising at the end of the sentence.

A

sentence which is ambiguous when it is written may be unambiguous when spoken.

For example :

1.

Tristram left direction for Isolde to follow.

If

Tristram wanted Isolde to follow him, the sentence would be pronounced with the

rise in pitch on the first syllable of follow, fllowed by a fall in pitch, as

in (2)

2.

Tristram left directions for Isolade to follow.

The

sentence can also mean that Tristram left a set of directions he wanted Isolde

to use. If this is the intention, the highest pitch comes on the second

syllable of directions as in (3) :

3.

Tristram left directions for Isolde to follow.

The

way we have indicated pitch is of course highly oversimplified. Before the big

rise in pitch the voice does not remain on the same low pitch. These diagrams

indicate merely when there is a special change in pitch.

The

primary function of intonation is to indicate sentence meaning, but many

linguist would also say that it has other functions. One is to signal the attitude

of the speaker. Feelings of anger, impatience, relief, surprise, and so on, can

all be expressed through intonation as well as by the words we use. For

example, the well-known Australian habit of ending a statement with a rise in

pitch indicates uncertainly usually a desire on the part of the speaker to

check that the message has been understood.

Although

we talk about intonation solely in terms of pitch contour, or direction, there

are other pitch features that affect our preception of sentences. Pitch range

(the degree of difference between the high pitches and the low pitches)

indicate emotional involvement. The range tends to widen with excitement, and

to narrow with boredom or wearniess. Pitch height tends to vary with the

familiarity of he context; the average pitch of the voice is often lower in

more intimate situations.

Such

variation in intonation is often parallelled by a difference in other prosodic

feature such as loudness; just as voice that is soft and low can signal warm

friendliness, loud tones with a raised pitch will often interpreted as

overbearing or aggresive. Rate of utterence serves several function. Variation

in the speed of talking may mark grammatical boundaries, indicate parenthetical

statements (‘Raelene’s boyfriend you know the one i mean called over last

nigh’), or may, like the other features, show differences in the intensity of

feeling.

Sentence

(4) can display a range of attitudes or ‘meaning’ depending on the prosodic

features which are associated with the words :

(4)

Come here

Varying

degrees of loudness, pitch range and height, combined with either fast or slow

utterance, will make the sentence sound peremptory, quietly menacing, or

resigned in tone, or could turn it into an intimate invitation. All these can

be expressed even though the pitch contour retains its standard falling pattern.

Word

stress

In English and many other languages, one or more of

the syllables in each content word (words other the ‘little words’ such as to,

the, a, of, and so on) are stressed. The stressed sylable is marked by an acute

accent ( ’) in the following examples :

These minimal pairs show that is contrastive in

English; it distinguishes between nouns and verbs.

In some words, more than one vowel is tressed, but if

so, one of these stressed vowels receives greater stress than the others. We

have indicated the most highly stressed vowel by an acute accent ( ’) over the

vowel (we say this vowel receives the accent, or primary stress, or main

stress); the other stressed vowels are indicated by marking a grave (`) over

the vowels (these vowels receive secondary stress).

Generally, speakers of a language know which syllable

receives primary stress or accent, which receives secondary stress, and which

syllables are not stressed at all; it is part of their knowledge of the

language. Sometimes it is hard to distinguish between primary and secondary

stress, but it is easier to distinguish between stressed and unstressed

syllables.

The stress pattern of a word may differ from dialect

to dialect. For example, in British and Australasian English the word

labo`ratory has only one stressed syllable; in most varieties of American

English it has two. Because the vowel qualities in English are closely related

to whether they are stressed or not, the British and Australasian vowels differ

from the American vowels in this word; in fact, the American version has an

‘extra’ vowel because of the way it is stressed.

Just as stressed syllables in poetry reveal the

metrical structure of the verse, phonological stress patterns relate to the

metrical structure of a language.

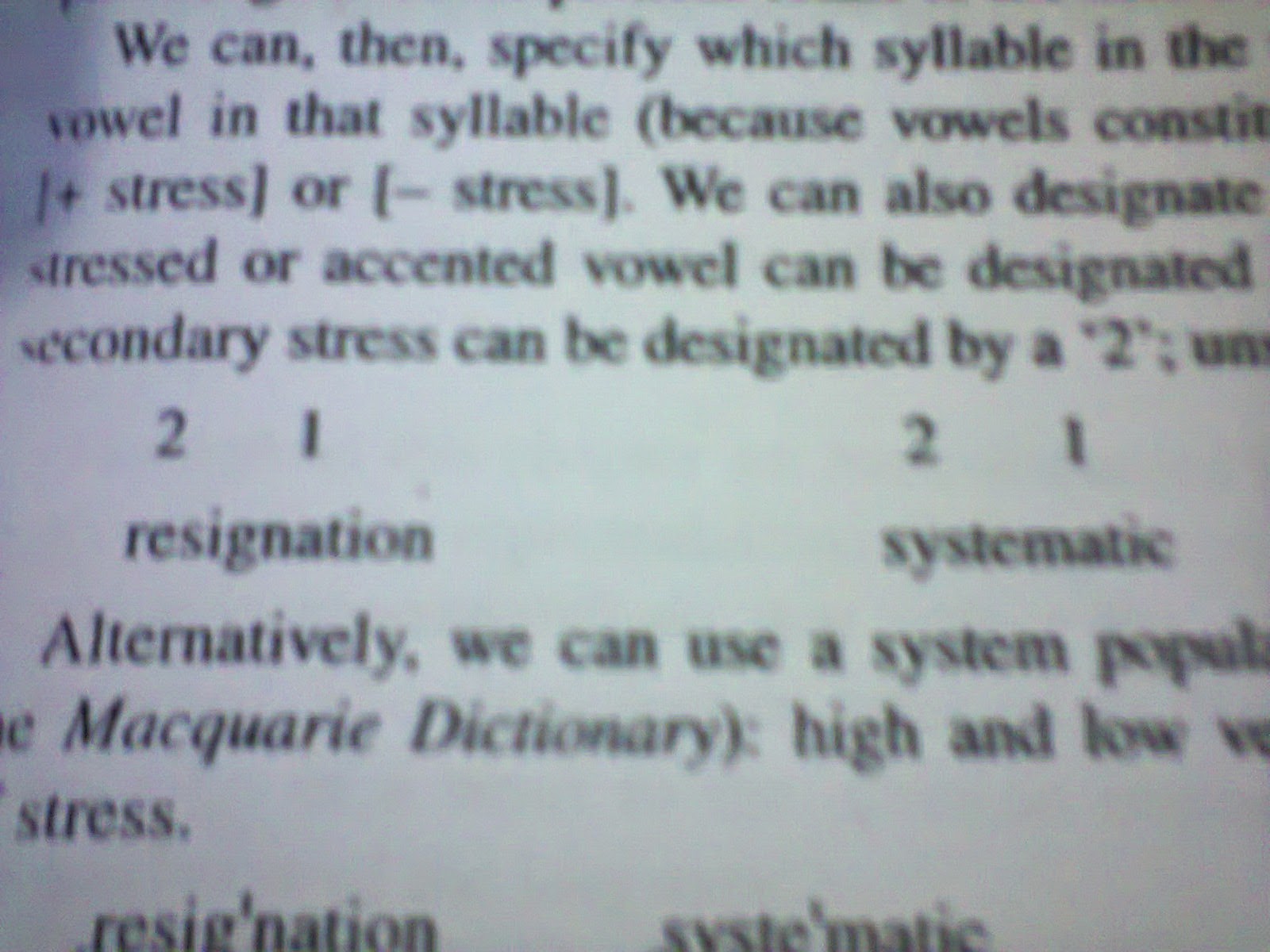

We can than, specify which syllable in the word is

stressed by marking the vowel in that syllable (because vowels constitute the

syllable peaks) as either [+ stress] or [- stress]. We can also designate

stress by numbers. The primary stressed or accented vowel can be designated by

placing a ‘1’ over the vowels; secondary stress can be designated by a ‘2’;

unstressed vowels are left unmarked.

Alternatively, we can use a system popular in many

dictionaries (including the Macquarie Dictionary): high and low vertical bars

indicate the two levels of stress.

Stress is property of a syllable rather than a

segment, so it is a prosodic or suprasegnental feature. Tone may also be a

property of a syllable rather than a single vowel; it, too, then, would be a

suprasegmental feature.

To produce a stressed syllable, we may change the

pitch (usually by raising it), make the syllable louder, or make it longer. We

often use all three of these phonetic features to stress a syllable.

Sentence

and phrase stress

When words are combined into phrases and sentences,

one of the syllables receives greater stress than all other. That is, just as

there is only one primary stress in a word spoken in isolation (foe example, in

a list), only one of the vowels in a phrase (or sentence) receives primary

stress or accent; all the other stressed vowels are ‘reduced’ to secondary

stress. A syllable that receives the main stress when the word is not in a

phrase may have only secondary stress in a phrase. Is illustrated by these

examples :

In English, we place primary stress on an adjective

followed by a noun when the two words are combined in a compound noun (usually,

but not always, written as one sound), but we place the stress on the noun when

the words are not joined in this way. The differences between the pairs above

are therefore predictable :

These minimal pairs show that stress may be

predictable if phonological rules include non-phonological information; that

is, the phonology is not independent of the rest of the grammar. The stress

differences between the noun and verb pairs (foe example, subject as noun and

verb) discussed in the previous section are also predictable from the word

category.

In the English sentences we used to illustrate

intonation contours, we may also describe the differences by referring to the

word on which the main stress is placed, as in the following examples :

1 Tristram left directions for Isolde to follow.

2. Tristram left directions for Isolde to follow.

In sentence (1) the primary stress is on the word

follow, and in sentence (2) the primary stress is on directions.